As 2012 marked the 125th anniversary of this often-overlooked chapter of U.S. history, the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience (The Wing) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) came together to open the doors to recognize a rich and robust slice of Asian pioneer contributions in the West.

In 2010, the Seattle museum and USFS sponsored the Chinese Heritage Tour of the American West to connect people with the vanishing past in a real way — by going to the places where history occurred. The tour began in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District and made its way through the windy roads, mountainous terrain and mining areas of Oregon and Idaho. It traveled through arid flatlands and mountains of Nevada.

Participants — who ranged from teenagers to the retired — walked on the same rock walls in mining areas that Chinese pioneers worked in the 19th century. Participants also visited the final resting ground for those who never returned to China. Centuries earlier, the Chinese served as merchants, miners, cooks and laborers. They arrived in a new, rugged and at times unforgiving place because of turmoil, poverty and need back home.

Their footprint in the West was wide, serving to keep the economies of towns and mining camps running when others had left. For the tour participants, the chance to see history face to face and touch the walls and places in the open air made for memorable moments.

Some participants wept, as they thought of their parents, grandparents and relatives — and were again reminded how Asian immigrant history becomes a pillar of the American Experience. There were eye-opening moments and quiet nods of realization that generations of Asian Americans are standing on the shoulders of those who came before them.

There also was an acknowledgement of the human instinct to survive. It is just that in the 21st century, the faces, names, language and homes of these Asian pioneers have long vanished from daily conversation.

These historic places, many on federal lands and in state parks, can still be visited. Some might be barren. But they are places in the American West in which visitors can explore and breathe new life — and return home with stories, moments and an awareness that will last forever.

Lake View Cemetery is regarded as “Seattle's Pioneer Cemetery.” Situated atop Capitol Hill with sweeping views east towards Lake Washington, the cemetery was incorporated on October 16, 1872 as the Seattle Masonic Cemetery.

While nature has taken back much of the townsite, vestiges still remain, including a large mechanism to turn railway cars around at the site. Archaeologists also have marked out areas of Monte Cristo, including quarters for Japanese American labor crews that helped build and service the railway line.

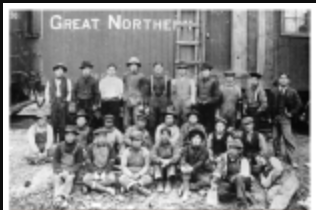

The Iron Goat Trail follows the abandoned Great Northern Railway with easy grades, accessible trails, beautiful views of surrounding mountains, educational interpretive signs and comfortable trailside benches.

The museum is in the heart of Seattle’s vibrant Chinatown-International District — a national historic district — and includes the very hotel where countless immigrants first found a home, a meal and refuge.

Pioneer Chinese American miners in Oregon and Idaho were placer miners, sifting by hand through the above ground tailings left behind by white miners churning through the land with large machinery to extract large loads.

The Ah Hee Diggings Interpretive Site vividly displays the mining efforts of Chinese American miners in the late 1880s.

A Chinese Cemetery was used for burials from 1880-1940. Some years after burial, most remains were exhumed and transported to China for final burial by previous arrangement...

Preserving the legacy of the Chinese workforce in Oregon, the Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site features an original building and contents of an early Chinese store and herbal doctor’s home and office.

Chinese American laborers were prohibited from purchasing land, but could buy claims or lease the rights to mining operations.

The museum tells the story of Idaho from pre-contact times through the fur trade, the gold rush, and pioneer settlement to the present.

Few were more successful than the Chinese immigrant Pon Yam, renowned for owning the largest diamond ring in the Boise Basin and referred to as the “King Merchant.”

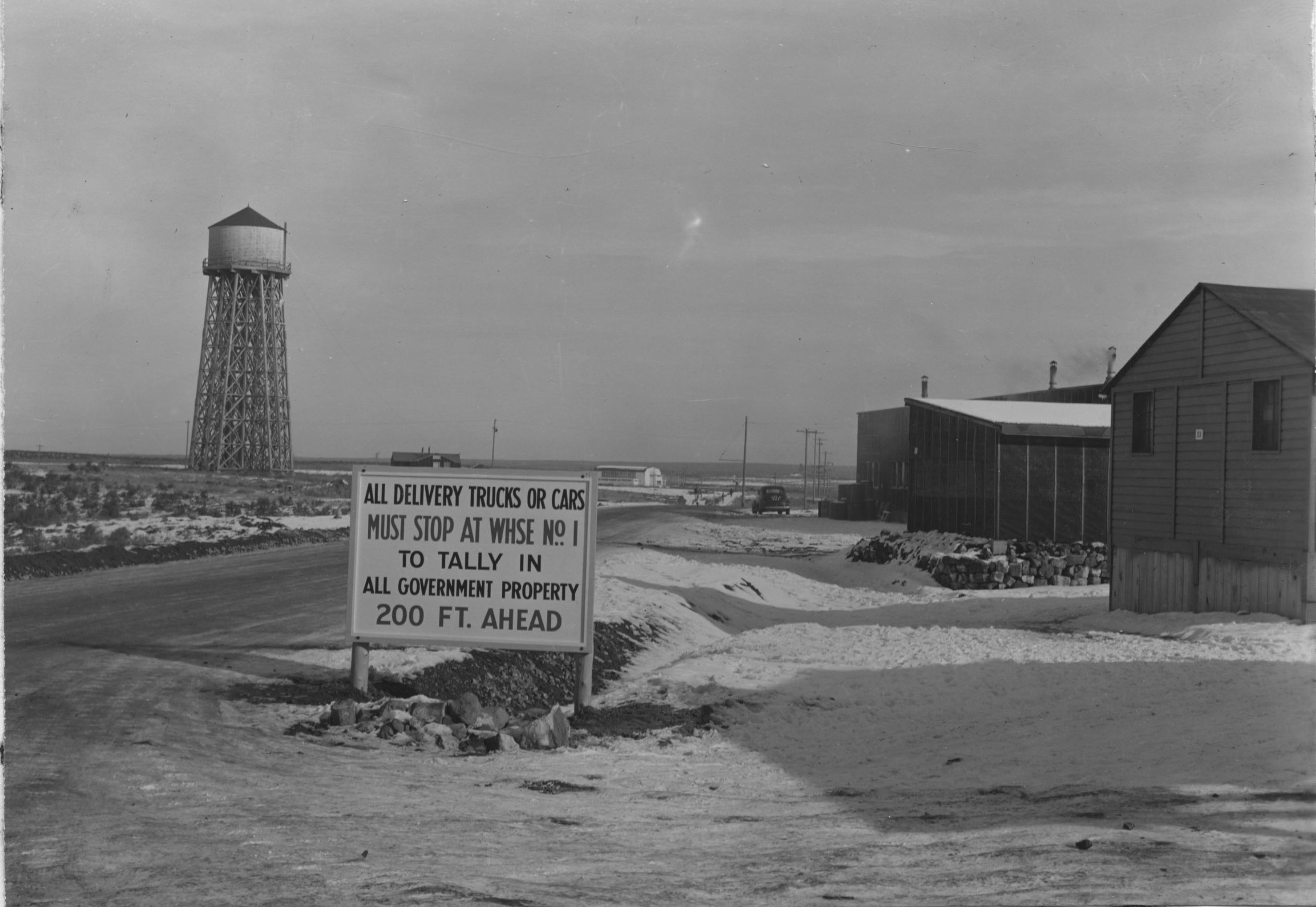

The Minidoka concentration camp was located in Jerome County, Idaho, 15 miles east of Jerome and 15 miles north of Twin Falls. It is also known locally as Hunt Camp, after the official Post Office designation for the area, since there was already a town of Minidoka in Idaho, 50 miles east.